Jean Luc Godard’s first feature feels oddly like a

swansong: in many respects the film seems a self-mockery of what it ostensibly celebrates

– the new, the bold, the reckless; the 60s zeitgeist that resurrects the

anguished ghosts of the 1920s, who, according to F. Scott Fitzgerald, grow up

to “find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faith in man shaken.” For the

children of the ‘60s, their wars are of a kind in which the opponents constantly

change roles: sometimes they are the unmerciful authorities bent on making

miserable lives out of their inferiors; in other times they are the society at

large, weeding out in its insidious and devious way the errant law-breakers. They

all seem to be donning the same masks, through which the warriors recognise

themselves.

This fight with one’s inner demon necessarily evokes concerns

of mortality and death - timeless concerns that acquire an added pungency in

the 1960s: would a dangerous, unheeding spell of hedonism finally defy life’s

incontrovertible law, or would it further precipitate death’s inexorable truth?

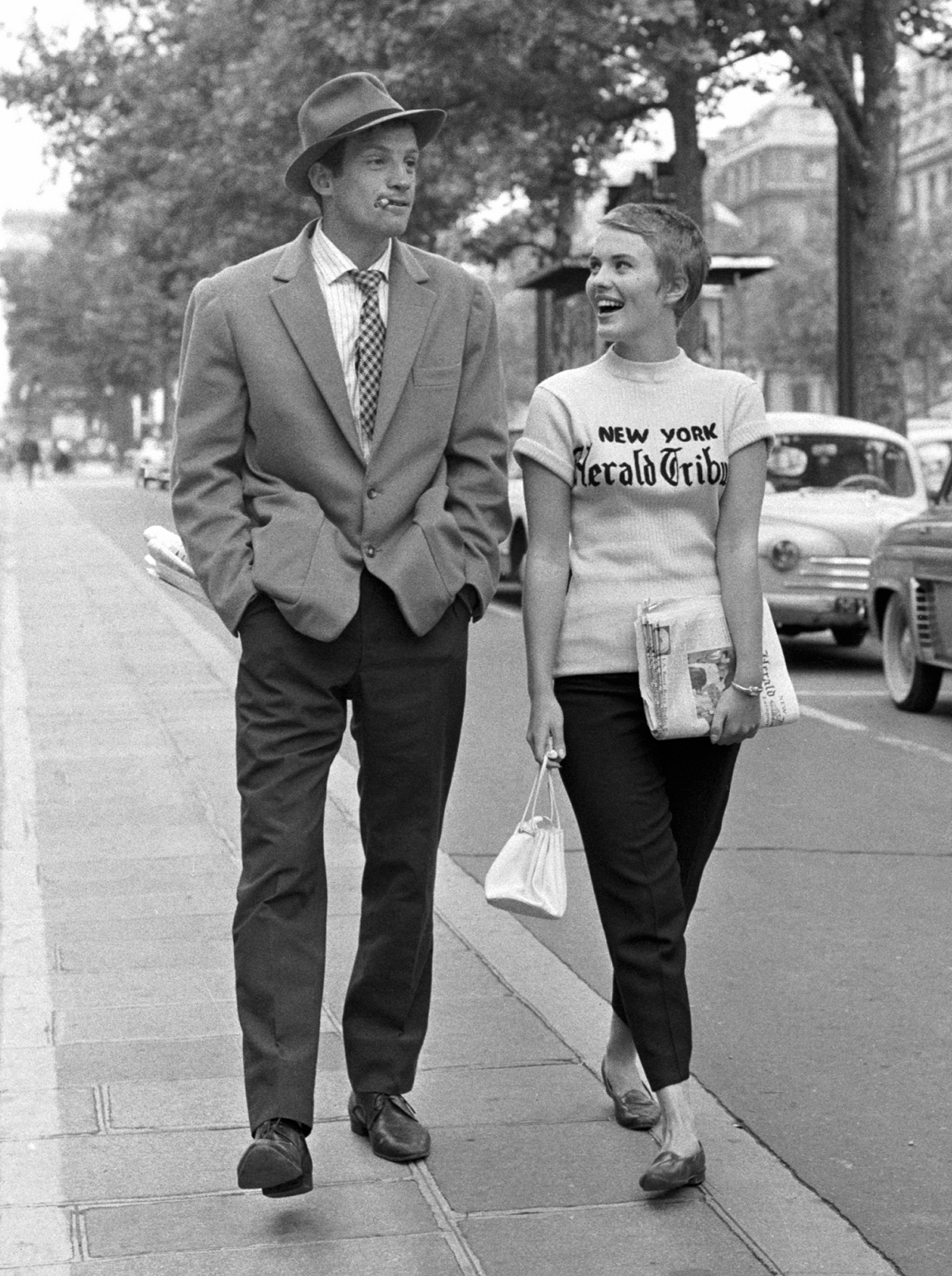

In Breathless, Jean Seberg’s

character, Patricia, reads from William Faulkner’s Wild Palms: “Given a choice between grief or nothing, I’d choose

grief.” What would you choose?, she asks Jean Paul-Belmondo’s Michel, who immediately

plumps for the latter, because grief is “stupid.” But he then adds: “Grief is a

compromise.”

That compromise is not a commendable attitude towards life’s

adversity, and is indeed antithetical to the idealism of the time, is a creed

that both Patricia and Michel, more unconsciously and insouciantly on her part

and more vigorously and insistently on his part, abide by. Michel is a

desperado at large for killing a policeman; he seeks refuge in the flat of his

American girlfriend, Patricia, who is pregnant with his child. This lovers-on-the-run

story borrows, and subsequently burlesques, many of the familiar tropes

implicit in such genre: the collision between ideal and reality, the continual

and ultimately futile fight against social inequality, the testing of loyalty

and fortitude, and the struggle against the incessant intrusion of human

elements. Worshipping the films of Humphrey Bogart, Michel consciously adopts

his idol’s rugged manner and perpetual snarl; but it is the heart that invariably

gives Bogart’s character away – his tough guy image proves merely an

unfortunate cover-up – as is what gives Michel away. He resigns to his fate in

the end, despite knowing that Patricia snitches on him, and refuses to run off.

His reasons? He genuinely falls for the girl and is simply too tired of always

being on the lam.

So compromise the hero finally bows to – the compromise

of one’s ideology and freedom for a love that one is hopeless to attain; the

compromise of one’s failing grasp on impalpable illusion for a palpable but

hitherto deferred notion of reality. Michel, playfully modelling his life on

the dramatic adventures which Bogart’s character generally undergoes, emerges

despite his eventual defeat – a predestined end long-deferred – as possessing the

kind of courage and bravery that, manifested all too often in Bogart’s films, can

only be summoned up by the comparably expansive hearts of the defeated. The

courage and the bravery to admit defeat, to consent to the inevitable passage

of life and death, to acknowledge one’s powerlessness to alter fate – these humbling

avowals are so absent from the victors’ thoughts because victory automatically affirms

the illusion of one’s immortal strength, further shoring up the false image of

a superhuman.

These matters of mortality and death are, however, not

yet within the radius of Patricia’s intelligence. During her interview with writer

Parvulesco (played by director Jean-Pierre Melville), she asks him his greatest

ambition. “To become immortal and then die,” a response to which Patricia registers

puzzlement, probably too young and inexperienced to know its meanings.

And what is immortality that is paradoxically embedded

within the finite extent of mortality? Clarice Lispector, in her short story “The

Egg and the Chicken,” clarifies the difference between living and surviving: “Surviving

is salvation. For living doesn’t seem to exist. Living leads to death…

Surviving is what’s called keeping up the struggle against life that is deadly.”

This formulates, for me, a most satisfying answer to the antinomy: that both surviving

and living constitute life’s immortal feats.

Comments

Post a Comment